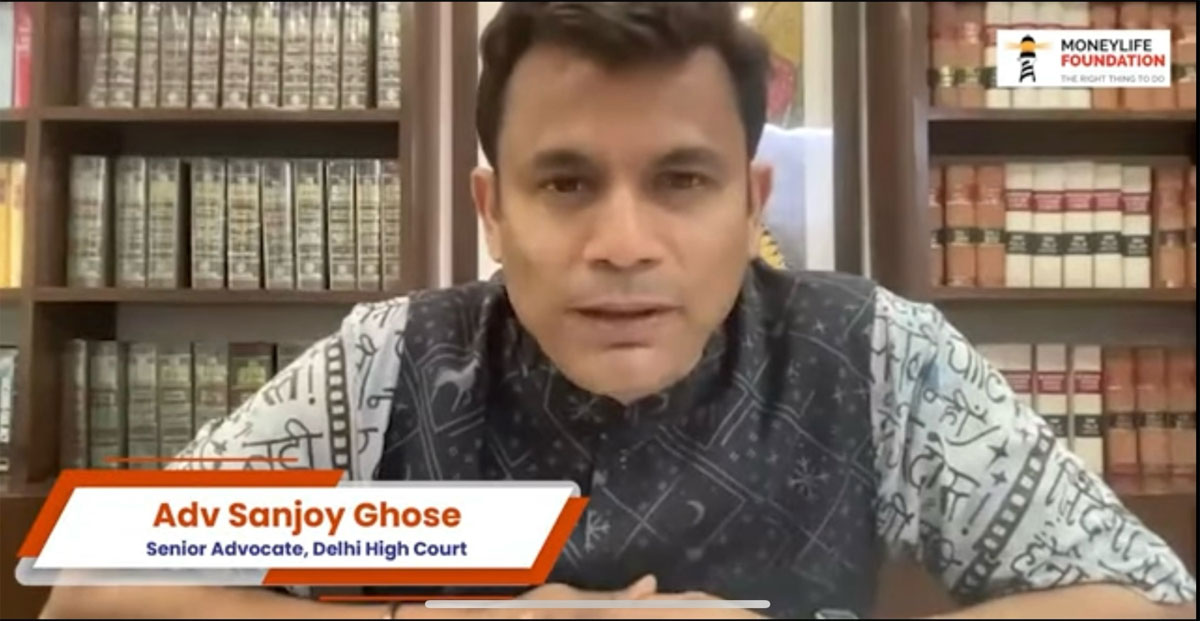

“The road to hell is paved with good intentions,” cautioned senior advocate Sanjoy Ghose in a recent webinar hosted by Moneylife Foundation. Adv Ghose, a veteran of the Delhi High Court, was dissecting the newly implemented Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) and Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA), which have replaced the colonial-era Indian Penal Code (IPC), Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) and Indian Evidence Act, respectively.

The webinar aimed to demystify these new laws for the public, highlighting both their intentions and potential challenges. While acknowledging the need for legal reforms, Adv Ghose expressed deep concerns about the hasty implementation of these sweeping changes. He likened the new laws to a “Mohammed bin Tughlaq-esque” approach, characterised by visionary ideas that are far ahead of their time but lack the necessary infrastructure to support them.

He pointed out that while the government touts the new laws as a decolonisation effort, a significant portion is essentially a rehash of existing provisions. The renaming of sections and introduction of new terminology could lead to confusion and delays in the legal process. He also noted a paradox where some new provisions may be more restrictive than their colonial-era counterparts, particularly in relaxing safeguards on police-interrogated evidence.

While the format and time constraints of the webinar did not allow Adv Ghose to critically analyse and comment on each section of the new laws, he did spend time highlighting potential areas of concern in some key provisions. For instance, he criticised the introduction of mandatory minimum sentences for certain offences, arguing that this could lead to a surge in acquittals as judges might be reluctant to impose harsh punishments without sufficient evidence.

The new laws have also expanded the scope of police powers. While the intention might be to expedite investigations, Adv Ghose warned of the potential for abuse, especially in cases involving marginalised communities and activists. The provision allowing police to conduct preliminary inquiries before registering FIRs, for instance, could lead to delays and even suppression of cases.

A particularly concerning aspect of the new laws, according to Adv Ghose, is the potential for overreach by the state. “The government has introduced provisions that could be misused to target dissent and stifle critical voices,” he warned. The vague definition of “hate speech” and the expanded powers of the police to conduct searches without stringent safeguards raise serious concerns about the erosion of civil liberties. Moreover, the provision for forfeiture of property for any criminal activity raises questions about the extent of state power and the potential for misuse.

Moreover, Adv Ghose cautioned about the potential for the new laws to create a two-tiered justice system. He emphasised the lack of provisions for legal aid and public defenders, which could disproportionately affect marginalised communities. He expressed concern about the increased discretionary powers granted to the police and the potential for these powers to be misused against marginalised groups such as activists, tribals and Dalits.

Adv Ghose further emphasised that any meaningful reform in the criminal justice system must be accompanied by comprehensive police reforms. “Insulating the police from political interference is crucial,” he asserted. Without a checks and balance system, the expanded powers granted to the police under the new laws could lead to abuse and misuse. The affluent and the powerful may be able to navigate the system more effectively, creating a stark disparity in the treatment of citizens before the law.

For instance, the new laws introduce provisions for community service as a form of punishment. While this could be a progressive step, Adv Ghose cautions about the potential for disparities in its implementation. Without adequate infrastructure and support, community service could disproportionately burden marginalised communities.

Adv Ghose also highlighted significant technological and infrastructural gaps that could hinder the effective implementation of the new criminal laws. He pointed out the disparity between the ambitious provisions outlined in the legislation and the ground realities of the Indian criminal justice system. For instance, while the laws incorporate provisions for electronic evidence and recording of crime scenes, the lack of widespread digital infrastructure and trained personnel to handle such evidence is a major concern. Additionally, the absence of adequate resources and manpower within the judiciary and police force could lead to delays, inefficiencies and potential misuse of the new powers granted to law enforcement agencies.

Addressing the rights of the accused, Adv Ghose also commented on the introduction of a trial in absentia in the new laws, and questioned whether such a trial for those absconding abroad, would be conduced at a level matching international standards of justice.

The implementation of the new criminal laws marks a significant turning point in India's legal landscape. While the intentions behind the reforms might be laudable, the potential pitfalls cannot be ignored. Adv Ghose’s analysis underscores the need for careful monitoring and evaluation to mitigate any unintended consequences. As he states, the success of these laws hinges on careful implementation, adequate training and a robust monitoring mechanism. In his opinion, there is a need for a holistic approach to criminal justice reform as “mere changes in laws are insufficient without corresponding improvements in infrastructure, police reforms and access to legal aid.”

Watch the Video Recording on Moneylife Foundation’s YouTube Channel: